Copyright © 2016

Transgender Law Center and Cornell University Law School LGBT Clinic

This guide may be used and reproduced without permission of Transgender Law Center and Cornell University Law School so long as it is properly cited. Excerpts may be taken if (a) they are properly cited AND (b) they are used within their proper context AND (c) a note is included that the excerpt is not legal advice.

Transgender Law Center

Transgender Law Center is the largest national organization dedicated to advancing the rights of transgender and gender nonconforming people through litigation, policy advocacy, and public education. TLC works to change law, policy, and attitudes so that all people can live safely, authentically, and free from discrimination regardless of their gender identity or expression.

Transgender Law Center Information

1629 Telegraph Ave, Suite 400

Oakland, CA 94612

p 415.865.0176

f 877.847.1278

[email protected]

Cornell Law School LGBT Clinic

The Cornell Law School LGBT Clinic (“the Clinic”) is one of only a handful of law school clinics fighting specifically for the legal rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. The Clinic provides free legal help to low-income LGBT individuals in a variety of cases, including immigration removal proceedings, asylum applications, appeals before the BIA, and family law, and prisoners’ rights matters. In addition to representing individuals in need of legal assistance, the Clinic undertakes advocacy projects in conjunction with other LGBT organizations to advance LGBT rights.

Cornell Law School LGBT Clinic

Susan Hazeldean

158 Myron Taylor Hall

Ithaca, NY 14853-4901

www.lawschool.cornell.edu/Clinical-Programs/lgbtclinic/

Cover Photo Courtesy of El/La Para TransLatinas

Introduction

This report’s purpose is to assess the country conditions in Mexico so that immigration judges and asylum officers can be fully informed about the issues facing transgender asylum applicants. This report examines whether recent legal reforms in Mexico have improved conditions for transgender women.[1] It finds that transgender women in Mexico still face pervasive discrimination, hatred, violence, police abuse, rape, torture, and vicious murder. These problems have actually worsened since same-sex marriage became available in the country in 2010. The report also suggests ways to improve the information about county conditions available to U.S. immigration judges and asylum officers so they can better adjudicate the asylum, withholding of removal, and Convention Against Torture claims of Mexican transgender women.

The Cornell Law School LGBT Clinic[2] and Transgender Law Center co-authored this report. The authors collected information for this report through news sources, academic research, expert witness testimony, and individual telephone interviews with advocates at non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Mexico and the United States. Transgender Law Center, a national organization based in Oakland, California, works to change law, policy, and attitudes so that all people can live safely, authentically, and free from discrimination regardless of their gender identity or expression. Transgender Law Center provides legal assistance and information to transgender individuals and their families and engages in impact litigation and policy advocacy to advance transgender rights. The LGBT Clinic at Cornell Law School is one of only a handful of law school clinics in the United States dedicated to serving members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community.[3] The clinic represents LGBT individuals in various legal matters and undertakes advocacy projects in conjunction with other LGBT organizations.

Executive Summary

Many transgender Mexican women seek asylum in the United States claiming that, because of their gender identity or expression, they will face rape, torture, or murder if they return to Mexico. In these cases, immigration judges and asylum officers must determine how likely it is that the asylum-seeker will face persecution if she is removed. Despite recent legal reforms in Mexico, legal advocates and individuals living in both Mexico and the U.S. report that rates of violence against transgender women are higher than ever. Specifically, violence against the LGBT community has actually increased since the recognition of same-sex marriage throughout Mexico because of backlash to these progressive changes in the law.

Despite the legal changes for same-sex couples in recent years, transgender women in Mexico still face pervasive persecution based on their gender identity and expression. Indeed, violence against LGBT people has actually increased, with transgender women bearing the brunt of this escalation. Changes in the laws have made the LGBT communities more visible to the public and more vulnerable to homophobic and transphobic violence. Increased visibility has actually increased public misperceptions and false stereotypes about the gay and transgender communities. This has produced fears about these communities, such as that being gay or transgender is “contagious” or that all transgender individuals are HIV positive. These fears have in turn led to hate crimes and murders of LGBT people, particularly transgender women.

Immigration judges in the United States often conflate the particular social groups of transgender women and gay men. Moreover, immigration judges sometimes give excessive weight to reports of minor societal advancements for gay communities in Mexico. Consequently, without thoroughly examining the actual conditions in Mexico for transgender women, immigration judges are not able to assess asylum cases fully and accurately.

The report recommends that information distinguishing between issues facing the gay and transgender communities be made available in Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) materials. For example, the EOIR can update their training modules with information about the transgender community specifically, so that judges can fully understand the distinct issues facing transgender women. In addition, applicants and their advocates can provide documentation of anti-transgender abuse to ensure that judges understand the issues specific to this community and make more sound findings in asylum, withholding of removal, and Convention Against Torture cases.

U.S Immigration System

Every year, thousands of Mexican citizens seek asylum or related forms of humanitarian relief in the United States.

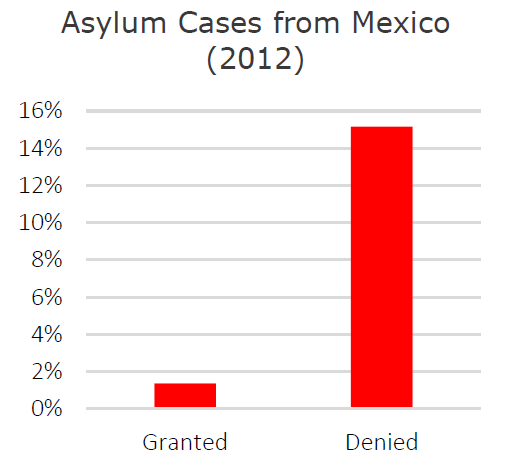

In 2012, U.S. immigration courts received 9,206 asylum applications from Mexican people.[4] That year, only 126 Mexican applicants were granted asylum by the immigration courts while 1,395 cases were denied.[5] The asylum office granted asylum to another 337 Mexican applicants.[6] There are no statistics on how many of those Mexican asylum-seekers were transgender people seeking asylum because they feared persecution based on their gender identity.[7]

Approximately 11.4 million Mexican immigrants live in the United States. Of those 11.4 million, approximately 51% are undocumented, 32% are permanent residents, and 16% are naturalized U.S. citizens.

An immigrant is eligible for asylum in the U.S. if she has a well-founded fear of persecution based on her “race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.”[8] The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) first recognized a gay man as a member of a “particular social group” in the 1990 In re Toboso-Alfonso case.[9] The BIA found that “homosexuals” in Cuba constitute a particular social group.[10] In 1994, the Attorney General designated the Toboso-Alfonso decision as “precedent in all proceedings involving the same issue or issues.”[11] Since then, several courts of appeal have similarly recognized “homosexuals” as a particular social group.[12]

In 2000, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decided Hernandez-Montiel v. INS, finding that a transgender person from Mexico qualified for asylum as a member of a “particular social group.” [13] But that decision did not refer to the applicant as transgender; the court instead called Hernandez-Montiel a “gay man with a female sexual identity,”[14] Hernandez-Montiel had lived as a woman since the age of twelve, took female hormones, and identified as “a transsexual.”[15] The immigration judge who initially decided Hernandez-Montiel’s case found her ineligible for asylum because he said she had not been persecuted on account of an “immutable” characteristic. Rather, the immigration judge found she could have chosen not to dress as a woman. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit found that Hernandez-Montiel’s identity as a “gay man with a female sexual identity” was either an “innate characteristic or one so fundamental to her identity or conscience that she either could not should not be required to change it.”[16] The court therefore held that Hernandez-Montiel was persecuted on account of her membership in a particular social group.

Obviously the decision to recognize Hernandez-Montiel’s eligibility for asylum was positive, but by defining her particular social group as “gay men with female sexual identities,” the court misleadingly conflated transgender women with gay men.[17] Some transgender women, including those from Mexico, may experience their gender identity and sexual orientation as interrelated in complex ways. Many transgender women who are attracted to men may go through a period of identifying as gay men, or being perceived by others as gay men, prior to coming out as transgender women. For some transgender women, the terms “gay” and “transgender” are not mutually exclusive categories, but overlapping, and they may use both terms to describe themselves. Regardless, when transgender women and feminine gay men face persecution, the root cause of both is likely the combination of cultural gender norms,[18] misogyny in general and the particular vitriol targeted at people who express femininity despite being assigned a male sex at birth.

Nonetheless, it is important for adjudicators to be aware that sexual orientation and gender identity are distinct components of identity.[19] Gender identity describes “each person’s deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond with the sex assigned at birth, including the personal sense of the body… and other expressions of gender, including dress, speech and mannerisms.”[20] Sexual orientation, on the other hand, is “each person’s capacity for… sexual attraction to, and intimate and sexual relations with, individuals of a different gender or the same gender or more than one gender.”[21] Transgender women are as diverse in their sexual orientations as non-transgender women. They may identify as straight, lesbian, bisexual, queer, or any other sexual orientation.[22]

When asylum decisions refer to transgender women as gay men with female sexual identities,[23] it is important to be aware that this may be an inaccurate and therefore disrespectful way of describing the individual’s gender identity. This inaccuracy can have serious and harmful consequences as it may contribute to misunderstandings regarding the deadly dangerous country conditions for transgender women in Mexico, as described below.

In 2015, in Avendano-Hernandez v. Lynch, a case of a transgender woman fleeing persecution and torture from Mexico, the Ninth Circuit recognized the error in conflating gender identity and sexual orientation and the harmful consequences of such a conflation.[24] In denying Avendano-Hernandez’s claim, the BIA had primarily relied on Mexico’s passage of laws protecting the gay and lesbian community, in particular the passage of same-sex marriage laws in Mexico City. In overturning the BIA, the Ninth Circuit declared the relationship between gender identity and sexual orientation to be distinct, though sometimes overlapping, and criticized the BIA’s analysis as “fundamentally flawed because it mistakenly assumed that [ ] laws [protecting the gay and lesbian community] would also benefit Avendano-Hernandez, who faces unique challenges as a transgender woman.”[25]

The court’s decision is explicit that laws recognizing same-sex marriage do little to protect a transgender woman from discrimination, harassment and violent attacks in daily life in Mexico.[26] The court also recognized that paradoxically, the passage of laws protecting the LGBT community in Mexico has actually worsened conditions for the LGBT community as the public and authorities react to expressions of sexual orientation and gender identity that the culture fears.[27]

The court ultimately granted Avendano-Hernandez relief on the record, reasoning that transgender persons in Mexico are particularly visible and vulnerable to harassment and persecution due to their public nonconformance with gender roles, that the Mexican police specifically target the transgender community for extortion and sexual favors, that there is an epidemic of unsolved violent crimes against transgender persons in Mexico, that Mexico has one of the highest documented numbers of transgender murders in the world, and that Avendano-Hernandez, who takes female hormones and dresses as a woman, is a conspicuous target for harassment and abuse.[28]

In order to establish her eligibility for asylum, an applicant must demonstrate that there is at least a 10% chance that she will experience harm that rises to the level of persecution.[29] If she can show that she was persecuted in the past, the applicant will be presumed to have a well-founded fear of future persecution unless country conditions have so improved as to negate her fear.[30] The persecution need not be inflicted by government officials; harm inflicted by private actors can also constitute persecution if the government is unable or unwilling to prevent it.[31] But in cases where a non-state actor is the persecutor, the asylum-seeker must show that she cannot avoid harm by moving to another region of the country.[32]

Generally, an applicant can only obtain asylum if she applies within one year of her last entry into the United States.[33] Unfortunately, the one-year deadline prevents many bona fide refugees from qualifying for asylum relief.[34] The only exceptions are granted when an applicant can show that a “changed circumstance” or “extraordinary circumstances” justified the delay in filing.[35] There is no exhaustive list of what might constitute changed or extraordinary circumstances, but serious mental illness or being an unaccompanied child have qualified as “extraordinary circumstances,”[36] and a recent HIV diagnosis, recently coming out as transgender, or progressing in one’s transition can qualify as a “changed circumstance” justifying a late asylum application.[37] Even if an applicant can show that she faced changed or extraordinary circumstances, she still must apply for asylum within a “reasonable” period of time.[38]

Applicants can seek asylum “affirmatively” by submitting an application to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) if they are not in removal proceedings.[39] Immigrants who are in removal proceedings before an immigration court must apply for humanitarian relief “defensively” by requesting asylum in the court proceeding.[40] People in removal proceedings can also apply for withholding of removal or relief under the Convention Against Torture (CAT).[41] These related forms of relief have higher burdens of proof and offer less protection than asylum, but they may be the only relief available to applicants who entered the U.S. more than one year from the time that they want to file for asylum and do not qualify for an exception to the one-year deadline[42] or for those with criminal convictions that bar asylum relief.[43] Being granted withholding of removal or relief under CAT protects the recipient from removal to the country where she would face persecution or torture, but it does not lead to permanent residency or citizenship.[44]

There is no time limit for applying for these forms of relief. An immigration judge must grant withholding of removal if the applicant is found to have a “clear probability of persecution in his or her country of origin, based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion,” provided no mandatory bars apply.[45] Immigrants in removal proceedings can receive relief from removal under the CAT if it is “more likely than not” that they will be tortured if removed from the United States.[46] Applicants can qualify for CAT relief even when their criminal convictions bar them from withholding of removal and asylum.

Laws Aimed At Protecting LGBT People In Mexico

The LGBT Community In Mexico

Mexico is a federal republic composed of thirty-one states and the Federal District of Mexico City. As of 2015, it has a population of approximately 121 million citizens.[47] Although there have been some prevalence-based studies attempting to assess the number of LGBT people in other countries,[48] there have been no federal population-based surveys, federal censuses, or national research studies assessing the LGBT population in Mexico. As a result, it is impossible to know the size of the Mexican LGBT community.

There are few population-based data sources that estimate the number of transgender people in any country.[49] Those that do exist suggest that transgender people constitute 0.1% to 0.5% of the overall population.[50] As such, transgender women likely constitute a small minority even within the Mexican LGBT community. Gathering data about the Mexican LGBT community is hampered by the fact that many individuals are reluctant to reveal their sexual orientation or gender identity because they fear harassment, violence, assault, and other negative societal consequences that may follow from such a disclosure.

Limited Antidiscrimination Laws.

Mexico has enacted antidiscrimination laws that forbid discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation at the federal level. In 2003, the Federal Congress passed the “Federal Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination” that includes “sexual preference” as a protected category. The law defines discrimination as:

Every distinction, exclusion or restriction based on ethnic or national origin, sex, age, disability, social or economic status, health, pregnancy, language, religion, opinion, sexual preferences, civil status or any other, that impedes recognition or enjoyment of rights and real equality in terms of opportunities for people.[51]

Article 9 of the law defines “discriminatory behavior” as:

Impeding access to public or private education; prohibiting free choice of employment, restricting access, permanency or promotion in employment; denying or restricting information on reproductive rights; denying medical services; impeding participation in civil, political or any other kind of organizations; impeding the exercise of property rights; offending, ridiculing or promoting violence through messages and images displayed in communications media; impeding access to social security and its benefits; impeding access to any public service or private institution providing services to the public; limiting freedom of movement; exploiting or treating in an abusive or degrading way; restricting participation in sports, recreation or cultural activities; incitement to hatred, violence, rejection, ridicule, defamation, slander, persecution or exclusion; promoting or indulging in physical or psychological abuse based on physical appearance or dress, talk, mannerisms or for openly acknowledging one’s sexual preferences.[52]

Various state laws also prohibit anti-gay discrimination.[53] It is important to note, however, that there are no federal laws that explicitly protect transgender individuals from discrimination on the basis of their gender identity (i.e., their transgender status) as opposed to sexual orientation. Mexico has also enacted legislation to protect women generally from gender-based violence.[54] But transgender women are not explicitly included in this legislation either.[55]

The National Council to Prevent Discrimination (CONAPRED) was created by the 2003 Federal Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination.[56] The agency is tasked with promoting policies and measures that contribute to cultural and social development, while advancing social inclusion. People who suffer discrimination committed by private individuals or by federal authorities can file a complaint with CONAPRED. When an aggrieved person files a complaint, the Council undertakes a settlement process between the parties. If they do not reach an agreement, CONAPRED can undertake an independent investigation. If it determines that human rights violations have been committed, it can order restitution measures including financial compensation, a public reprimand of the offender, a public or private apology, and a vow from the offender to never repeat the act. About 60% of cases filed regarding sexual orientation discrimination in 2009-10 were resolved by conciliation.[57] In 2010 CONAPRED forwarded 53 complaint files about anti-gay discrimination to the Public Ministry, which found them to be unlawful discrimination.[58]

Despite the existence of these formal protections around sexual orientation, advocates maintain that these laws have not prevented discrimination and violence.[59] LGBT individuals face many barriers in exercising their rights under the antidiscrimination statutes. LGBT individuals who experience discrimination may be afraid to disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity to a federal agency and may be concerned about potential retaliation by public officials. This concern is especially relevant since the law does not have a clear enforcement mechanism or any provision that protects against retaliation.

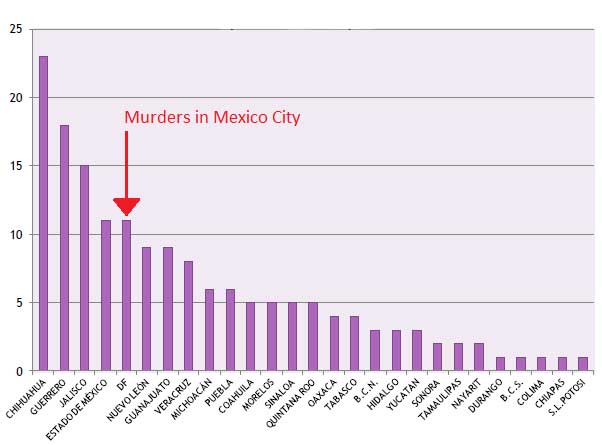

The adoption of the antidiscrimination laws is certainly a positive step, but it is far from clear that their enactment has actually led to an improvement in the treatment of LGBT people generally or transgender women in particular. For example, although Mexico City has an agency charged with receiving discrimination complaints, from January 2012 to April 2013 the agency had received only one official complaint of human rights abuse against a transgender individual.[60] During the same period there were at least eight violent murders of transgender women in Mexico City.[61] In fact, despite having the greatest number of legal reforms for and businesses catering to non-transgender gay people in the country, Mexico City “has the highest total” number of “homicides of LGBT people due to homophobia or transphobia.”[62]

The absence of any complaints is likely due to the myriad reasons transgender women do not report when they are victims of discrimination or hate crimes: concerns about disclosing sexual orientation or gender identity, fears of retaliation, lack of confidence in national agencies, a long history of corruption in Mexican investigative agencies, and doubts about the agency’s ability to investigate and remedy these violations.

As noted, federal antidiscrimination laws only provide explicit protections based on sexual orientation and do not protect against gender identity discrimination. Moreover, these federal antidiscrimination laws do not protect transgender communities from persecution because the Mexican government is unable to enforce them, especially because the police themselves are often the perpetrators of violence against transgender people.[63] Transgender women victimized by such violence are also unlikely to report the crimes because they fear retaliation from police or believe police will not accurately investigate their claims.

Limited Same-Sex Relationship Recognition

Mexico has also adopted laws granting rights to people in same-sex relationships. In 2006, Mexico City’s legislature approved the “Ley de Sociedades de Convivencia” (Law Regarding Cohabitation Partnerships) which allowed civil unions between same-sex couples.[64] On December 21, 2009, the Legislative Assembly approved legislation allowing same-sex marriage in Mexico City.[65] The bill changed the definition of marriage in the city’s Civil Code from “a free union between a man and a woman” to “a free union between two people.” [66] The law also allows same-sex couples to adopt children, apply jointly for bank loans, inherit from one another, and be included in spousal insurance policies. In August 2010, the Mexican Supreme Court held that same-sex marriages registered in Mexico City must be recognized in all of Mexico.[67] In July 2015, the Mexican Supreme Court released a “jurisprudential thesis” that effectively legalized same-sex marriage in all thirty-one states in Mexico.[68]

However, formal statutory advances for same-sex couples in Mexico have not reduced persecution against transgender women. In fact, as discussed in more detail later in this report, transgender women have borne the brunt of a violent backlash against same-sex marriage and other such advances. They are at a particularly intensified risk of persecution both because they are often imputed to be gay men and because they are vilified, stigmatized, and brutalized for being transgender women. This increased vulnerability also occurs because transgender women “may be more visible [and] viewed as more transgressive of social norms.”[69]

Name Change Rights

Mexico City has created some avenues for transgender people to conform their identity documents to their gender identity. In 2004, Mexico City amended its Civil Code to permit an individual to change the name and gender marker on their birth certificate.[70] Specifically, the Mexico City Civil Code was amended to allow modification of a person’s birth certificate “upon request to change a name or any other essential data affecting a person’s civil status, filiations, nationality, sex and identity.”[71] In 2014, Mexico City also passed a law that permits transgender individuals to legally change their gender without a court order.[72]

Lack Of Legal Protectors For Transgender People.

As described earlier, transgender women have limited formal legal protections in Mexico against discrimination and hate crimes. Only Mexico City has an antidiscrimination law that explicitly protects against gender identity discrimination.[73] Other protections that exist exclusively in Mexico City include name changes, legal recognition of gender changes,[74] and specialized healthcare for transgender people.[75] Transgender women continue to experience pervasive discrimination in public and in their private lives.[76] Even a representative of CONAPRED stated that “tolerance towards groups such as homosexuals is still ‘practically the same’ even after the State [Mexico] recognized their rights.”[77] The 2013 U.S. State Department Human Rights Report on Mexico stated that “discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity was prevalent[.]”[78] It also noted that “the government did not always investigate and punish those complicit in abuses.”[79]

Transgender women often do not report hate crimes or police abuse because the authorities rarely investigate these crimes.[80] When the police do get involved, they frequently minimize the crime and mischaracterize it. For example, in violent murder cases the police usually determine that the cases are “crimes of passion” instead of hate crimes.[81] Holding police and military abusers accountable is also difficult.[82] The process for punishing the police and military is “extremely slow and inadequate.”[83] Transgender women avoid reporting police abuse out of fear of police retaliation against them or their family members. [84] Further, human rights commissions tend to be anti-LGBT and will often disregard complaints by transgender women.[85] Transgender women cannot depend on inadequate and ineffective laws penalizing hate crimes to protect their rights.

Morality Laws

Some Mexican communities have explicitly targeted transgender women by enacting morality laws that criminalize “cross-dressing.” In 2002, the city of Tecate, Mexico amended its Police and Good Governance Code to prohibit “men dressed as women in public spaces.”[86] This revision “was coded in terms of infractions against morality.”[87] Upon passing the law, the mayor of Tecate stated that Town Hall officials and the majority of the population supported it.[88] A coalition across the political spectrum spoke out in favor of the morality law.[89]

Supporters stated that Tecate’s prohibition of gender nonconformity was needed to protect against social disturbance; they regarded “cross-dressing” as a threat to order, morality, harmony, mutual respect, and children.[90] They implied transgender women were pedophiles. In explaining his support for the law, counsel advisor José Luis Rojo claimed that transgender women disrupt the public peace and “take advantage of children.”[91] A senior councilman, Cozme Casares, added that he and others supported the measure because they believed it would prevent the spread of AIDS and sex work.[92]

Local transgender women reported a dramatic increase in police harassment following the law’s passage. A woman named Gabriela reported that a police officer had “pulled [her] out of the doorway of a pool hall by her hair.”[93] Transgender women were frequently accused of being involved in sex work, even when they were simply running errands like going to buy milk. Transgender women stopped by the police frequently faced extortion; “[t]he police used… the threat of arrest… to secure money or sexual favors from [transgender women].”[94] The passage of morality laws like those in Tecate criminalizes transgender women and sanctions police harassment and private discrimination. The passage and retention of these laws reflect continued societal hostility towards transgender people.

Expansion Of LGBT Rights Has Led To Backlash

Violence and discrimination against the LGBT community remains pervasive throughout Mexico.[95] Legal recognition of same-sex couples has increased societal awareness of the LGBT community and made LGBT people much more visible. Ironically, increased awareness of LGBT people appears to have produced significant backlash.

Violence Against Transgender Woman

In order to win asylum, an applicant must show she has a well-founded fear of persecution either from state actors or from private parties that the government is unwilling or unable to control.[96] Even if Mexico’s prohibition of anti-gay discrimination and enactment of some formal protections for same-sex couples could be read to indicate that certain authorities are willing to prevent anti-gay abuse (or, more accurately, that they are willing to pay lip service to the notion of protecting LGBT people), it does not necessarily mean that the Mexican government is able to protect LGBT people generally or transgender women specifically from the horrific violence they face. In fact, many transgender women face violence from government actors themselves, often in the form of abuse from police and harassment by the military.

Since Mexico recognized same-sex marriage in 2010, several prominent advocates in the transgender community have been brutally murdered.[97] Many of these killings occurred in Mexico City, despite its adoption of a hate crimes statute and antidiscrimination laws. In 2010, a Mexican National Survey about discrimination found that 83.4% of LGBT Mexicans had faced discrimination because of their “sexual preference.”[98] In 2011, the same survey reported the principal basis of discrimination was “sexual preference.” [99] In 2012, however, “gender identity” was the most frequent basis for discrimination, showing the growing rates of discrimination against the transgender community.[100] It is clear that the Mexican government is unable to effectively protect transgender women.

Transgender women regularly experience harassment and hate crimes at the hands of members of the public. The following are only a few examples of the many atrocities that transgender women have experienced in Mexico. A prosecutor in Chihuahua belittled a transgender woman who sought redress for abuse and violence she experienced, asking her, “So why are you walking in the streets?”[101] In November 2011 in Chihuahua, a group of men kidnapped two transgender women in Hotel Carmen.[102] Days later, the dismembered bodies of these women were found in a van.[103] In June 2012 in Mexico City, the body of a transgender woman was dismembered. Her remains were found abandoned in different neighborhoods in the Benito Juarez district.[104] In June 2013, police found the body of the transgender woman who headed the Special Unit for Attention to Members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Transgender, Transsexual and Intersex (LGBTTTI) Community of the Attorney General of the Federal District (PGJDF).[105] In July 2013, two attackers released pepper spray into a crowd of 500 at a beauty contest for transgender women.[106]

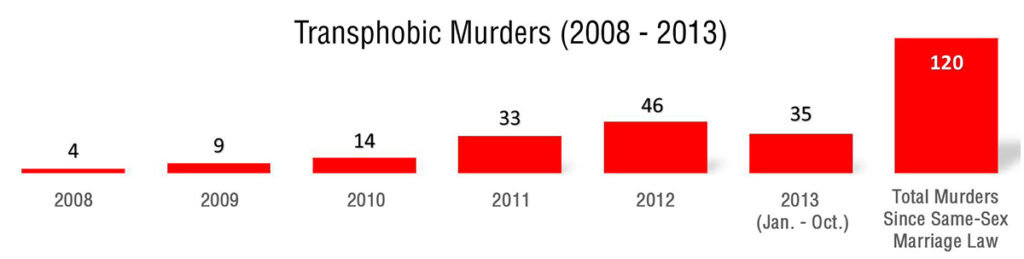

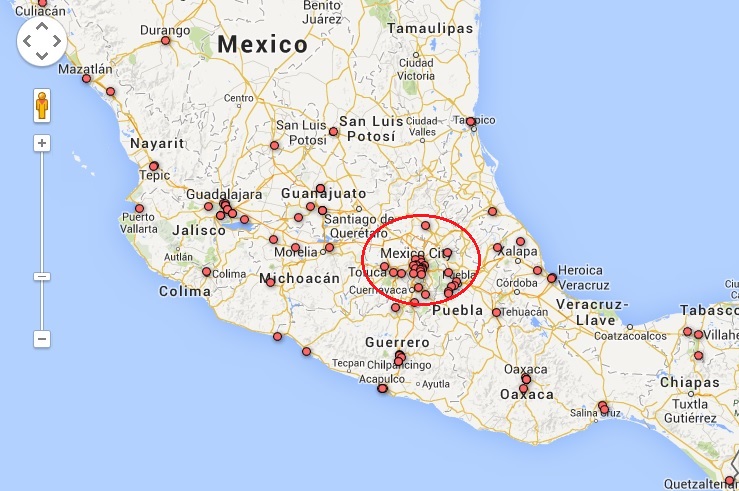

Geographical depiction of transphobic murders in Mexico between 2008 and 2013.1 Note that many have occurred close to Mexico City (Districto Federal).

Mexico has the second-highest index of crimes motivated by transphobia in Latin America, behind Brazil.[107] Reports of hate crimes—particularly transphobic murders—continue to rise,[108] including in Mexico City.[109] Most hate crimes against the LGBT community go uninvestigated.[110] In many instances, police dismiss investigations of homophobic and transphobic murders by categorizing them as “crimes of passion.”[111] Indeed, it is estimated that almost 90% of crimes in Mexico go unreported.[112] It follows then that the actual number of transphobic murders in Mexico is likely much higher.

It is also critical to note that all members of the LGBT community are not similarly situated when it comes to homophobic and transphobic violence and persecution. In fact, some LGBT people are far more vulnerable than others. Transgender women are particularly likely to be singled out for abuse. Even in the United States, transgender people report far higher rates of violence and mistreatment than non-transgender lesbians and gay men.[113] In Mexico, transgender people are “heavily stigmatized and discriminated against, even by members of the gay community.”[114] It is therefore important to avoid erroneously conflating the experiences of non-transgender lesbian and gay people with those of transgender women. For example, in Lopez-Berera v. Holder, the BIA affirmed the denial of asylum to an HIV-positive transgender woman from Mexico, inappropriately relying on dicta from a case about healthcare access for gay men.[115] On appeal, the government filed an unopposed motion to remand the case to the BIA for reconsideration.[116] Adjudicators must always examine evidence for the particular social group of transgender women and not deny asylum based on modest improvements in legal rights for non-transgender gay people.

In 2011, the year following the implementation of same-sex marriage across the country, there were more hate crimes against transgender people than in any year in recent history.[117] Activists were particular targets of this backlash.[118] On May 3, 2011, an LGBT activist named Quetzalcoatl Leija Herrera was found beaten to death.[119] In July 2011, Cristian Ivan Sanchez Venancio, a member of the Revolutionary Democratic Party’s Coordinating Group for Sexual Diversity and an organizer of Mexico City’s annual LGBT Pride march, was found stabbed to death.[120] On July 6, 2011, men in two vehicles opened fire on a group of transgender women in Chihuahua killing one and wounding several.[121] In the state of Veracruz, activists noted that not only were LGBT people being killed at a high rate in 2011, but they were also increasingly being tortured before their deaths.[122] On August 18, 2012, a transgender woman was found dead on the street in a suburb of Mexico City. She had been beaten horribly and then decapitated.[123]

164 Assassinations in

27 States (2007 – 2012)

Of the transphobic murders between 2007 and 2012, many took place in Mexico City (DF), where the city has enacted same-sex marriage laws and laws allowing transgender individuals to change the gender markers on their birth certificates.[124]

Recent Transphobic Murders Of Prominent Transgender Women

“The paradox is that as the LGBT community makes these advances in Latin America, there appears to be higher levels of violence against them . . . . It seems to be a backlash and may be due to the greater visibility of LGBT communities. In a sense, the violence is a symptom of the achievements made by the movement.”[125]

Barbara Lopez Lezama[126]

Ms. Lezama was murdered on April 30, 2011. The assailant strangled her with a cord and inflicted blunt force trauma to her head. She was 24 years old. Barbara worked as a stylist and enjoyed knitting. Barbara was also active in the community: she worked with street children and those who were living with HIV/AIDS.

Agnes Torres Sulca[127]

Ms. Torres Sulca was found murdered in a ditch outside of Puebla on March 12, 2012. Her throat had been slashed and there were several burn marks across her body. Ms. Torres Sulca was a 28-year-old psychologist and educator and is remembered as an activist and ardent defender of human rights in Mexico’s LBGT community. Authorities closed her case in three weeks without identifying the perpetrator.

Hilary Molina Mendiola[128]

Ms. Mendiola was murdered on September 23, 2013 in Mexico City. She was pulled from a vehicle and thrown off a bridge by two men.

Virgen Castro Carrillo[129]

Ms. Carrillo, a 30-year-old transgender woman, was murdered sometime between March 19 and March 21, 2009. Ms. Carrillo was from Sinaloa, Mexico. Her body was found in the Tamazula River. After conducting an investigation, police suspected that a man killed Ms. Carrillo for being transgender and then threw her body into the river.

Fernanda Valle[130]

On June 19, 2010, Fernanda Valle, the Vice President of Transgénero Hidalgo (Transgender Hidalgo) “disappeared.” Ms. Valle’s body was eventually found tied up and tortured with two bullets in the head. The President of Transgénero Hidalgo, Karen Quintero, demanded a full investigation, but the Hidalgo authorities did not adequately investigate the crime.

Police Violence

Transgender women in Mexico face brutal violence not only from private citizens, but also from state officials. Police officers and the military subject transgender women to arrest, extortion, and physical abuse.[131] Many transgender women have been victims of police violence or know someone who has been a victim.[132] According to Victor Clark, professor at San Diego State University and the director of the Binational Center for Human Rights in Tijuana, Mexico, the police and military are the “primary predators” targeting transgender women.[133] Mexican police target transgender women and arbitrarily arrest them for pretextual reasons[134] such as “disturbing the peace” because they were wearing female clothing; for being perceived to be sex workers even if they were not; for failing to carry a valid health card; for allegedly carrying drugs; or for being said to be gay.[135]

For example, in March 2014, police officers in Chihuahua, Mexico arrested five transgender women for not carrying a health card, even though this is not a crime.[136] At the police station, male police officers forced the transgender women to undress in front of them.[137] The police then illegally forced the women to take HIV tests.[138] The police held the transgender women in jail for 36 hours and demanded 200 pesos from each woman for release.[139]

For decades the Mexican police forces have been implicated in cases of arbitrary detention, torture, and other human rights violations that are often unpunished.[140] Police officers often extort transgender women for sex or money in return for not arresting them or for releasing them from jail.[141] Many transgender women have to pay almost daily bribes to avoid being arrested.[142] A 2010 study by the National Council for the Prevention of Discrimination (Consejo Nacional Para Prevenir la Discriminación) reported that 42.8% of LGBT interviewees indicated that the police are “intolerant” of sexual minorities.[143] In a 2008 study by Mexico City’s Human Rights Commission, 11% of LGBT persons reported experiencing threats, extortion, or arrest by police because of their sexual orientation.[144]

A transgender woman in Tijuana, Mexico, reported the police abuse she suffered after being arrested to the Binational Center for Human Rights in Tijuana: “I was working as a sex worker, talking with a client, [when] the municipal police arrived and asked me for my identification documents. Everything was in check, [but] they [the police] accused me of being outside of the area [sex work tolerance zone] and arrested me, handcuffed me, and took me to a municipal judge. The police talked with the judge in codes and took me to the 20 [municipal jail]. They [the police] put me in a cell with 20 men all of whom were mocking me. I paid 600 pesos to the guards to not undress me.”

Military Violence

The military in Mexico continues to commit human rights violations against the civilian population across the country, including against transgender women. Former president Felipe Calderon (2006-2012) waged a “War on Drugs” and ordered the military to combat drug cartels and organized crime. However, instead of ensuring peace for civilians, the military has itself inflicted harm in areas of increased militarization. Soldiers assigned to policing and public security tasks often lack sufficient training to properly take on law enforcement roles.[145] Often, soldiers operate under militarized rules of engagement and use of force that increases the likelihood of mistreatment of civilians.[146]

Transgender women were already visible targets for police and military abuse, but once increased militarization began under Calderon, transgender women suffered increased aggression. Military troops engage in the same abuses as the police by making transgender women the object of arbitrary arrests, beatings, extortions, and robberies.[147] In May 2007, for example, members of the Military Police beat approximately 40 transgender women in Ciudad Juarez, leaving them hospitalized and in serious condition.[148]

Mercedes Fernandez, president of the Chihuahua Lesbian Gay Movement, described conditions for transgender women who face military persecution: “They [transgender women] can’t even go and buy their groceries because they are immediately transferred to the authorities where they are accused of engaging in prostitution. They take them away even if they are holding their grocery bags. They don’t have liberty of movement.”[150]

In the article “Abuses Against Transsexuals in Ciudad Juarez Continue to Rise,” Deborah Alvarez, a transgender activist declared:

“They [the military] pick up girls [transgender women] for no reason, they come into their apartments, slap them, insult them and push them.”[149]

Human rights violations by the military continue under the current president Enrique Peña Nieto, who took office in 2012.[151] Like the police, the military is rarely punished for the abuses reported by transgender women. Further, the military command structure prevents accountability for abuses.[152] The government instead punishes the victims of military violence by accusing them of criminal acts and blaming the victims for the harms they suffered at the hands of the military.[153]

Drug Cartel And Gang Violence

In 2012, drug cartels and gangs were responsible for the vast majority of killings and abductions in Mexico.[155] In July 2013 the government reported that, of 869 victims of homicides related to organized crime in the previous month, 830 were themselves allegedly responsible for crimes.[156]

Police often work with the cartels and gangs, with 98% of all crimes going unpunished. Vulnerable communities, including transgender women, are often victims of drug cartel and gang violence. Transgender women fall victim to cartel kidnappings, extortions, and human trafficking. One transgender woman described how cartel members forced her into sex work in Merida. Another transgender woman was targeted for rape and robbery while traveling by bus.[157] In another case, a transgender woman named Joahana in Cancun was tortured to death by drug traffickers who carved a letter “Z” for the Zeta cartel into her body.[158] If a cartel targets a transgender woman, it is nearly impossible to escape the cartel’s power. An immigration attorney in the U.S. described in an interview how his transgender female client unknowingly dated a cartel member. After doing so, she could not escape persecution from the cartel.[159]

Ana Frutos, a transgender woman from Guadalajara, testified before a U.S. Asylum Officer: “Even though I knew I would be an easy target for police and gang abuse, I made my transition to womanhood because my identity as a woman is what defines me. For me, hiding my true gender identity is impossible.”[154]

Links Between Mexican Government, Police and Organized Crime

The Mexican government and cartels have been linked numerous times to incidents involving human rights violations, and cartels have been revealed to be successfully infiltrating police and military forces. In 2009, three officers from the Attorney General’s Organized Crime Investigations Unit (SIEDO) along with ten soldiers were arrested for their ties to organized crime, with the acknowledgment that there were still many officers with probable ties to cartels.[160] Other officials with ties to organized crime include Héctor Santos Saucedo, then-head of Coahuila’s state investigations, who was connected to the notorious Zetas in 2010.[161] Occasionally the extent of the connection is not revealed until years later, such as with the San Fernando massacres carried out in Tamaulipas in 2010-11. In 2014 a freedom of information request revealed there were “direct links between the San Fernando police, the Zetas and the San Fernando killings.”[162]

The disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa in 2014 and their parents’ subsequent refusal to accept the half-answers from the government have put a spotlight on the connection between police and organized crime. The first reports indicated that the students were seized by local police acting on orders from the corrupt mayor of Iguala and then turned over to a local drug gang; however further information has begun to indicate that federal police were likely involved in the incident.[163] Transgender women, who already find themselves to be targeted by police and cartels separately, are even less likely to report any discrimination or violence they experience if they risk being targeted by the organizations that they are reporting against.

Societal Factors That Lead To Violence Against Transgender Women

“To society, I am not a person. To society, I am trash—do you understand?”

– Anonymous transgender woman in Mexico.[164]

Negative attitudes towards the LGBT community remain very common in Mexico.[165] Homophobic and transphobic comments from public figures, such as former President Felipe Calderon, diminish the quality and dignity of transgender women’s lives by perpetuating widespread hatred and violence.[166] There is also a nationwide backlash against advances in LGBT rights, resulting in increased levels of persecution against transgender women who tend to be the most visible and marginalized members of the LGBT community.[167]

Family Rejection

Many transgender women face abuse and rejection at the hands of their own families. The abuse ranges from physical, verbal, and sexual attacks to murder.[168] A recent survey of transgender women in Mexico City found that 45% had experienced abuse from their families.[169] As many as 70% transgender women and girls in Latin America are estimated to run away from or be thrown out of their homes.[170] The consequences of such family rejection include psychological trauma and emotional suffering, which often lead to mental health problems, suicide attempts, failure to complete education, and unemployment.[171]

A transgender woman named Yokanza Martinez Balez of Puebla described the rejection she faced after her transition in an interview with a journalist.[172] Ms. Martinez Balez began living as a woman at the age of 15. Her family forced her to leave home. She dropped out of high school, migrated north to Sonora, and became a sex worker.[173]

Another transgender woman, Gaby Morales Arellano, was forced by her parents to leave home shortly after she began transitioning to live as a woman.[174] Her dreams of becoming a lawyer ended because she had to take whatever job she could to survive.[175] She explained, “There is a lot of discrimination when you come out of the closet and you face all of these critics, first your family and your neighbors who say, ‘Why is he like that? He should be normal.’ My family thought they could beat me and correct me.”[176]

Another Mexican transgender woman who fled to the United States and sought asylum did so to escape severe physical and mental abuse from both her family and her community. She had sought help from the police in Mexico, but they ignored her pleas for protection. Without protection from her family or the police, gang members beat her severely and left her bleeding from head wounds. Fearing for her life, she fled to the United States, where she was able to receive asylum.[177]

Gender-Based Violence

Violence against women is very prevalent in Mexico, particularly in the forms of domestic violence and murders (femicide). According to a 2012 report by the Mexican Secretary of State, the number of female murder victims increased dramatically over the previous three years, particularly in the states of Chiapas, Chihuahua, Durango, Guerrero, Michoacan, Oaxaca, Sinaloa, Sonora, and the Federal District.[178] While Mexico has enacted statutes criminalizing domestic violence and femicide, their rates remain high.[179] In a 2012 study, researchers reported that 67% of Mexican women had been the target of a crime.[180] Despite the government’s effort to eliminate violence against women by enacting these protective laws, women continue to be subjected to violence and femicide at staggering rates.

Violence against non-transgender women is relevant to assessing conditions for transgender women because both populations experience high rates of gender-based violence that the Mexican government has been unable to control or prevent. Indeed, the overwhelming number of non-transgender women being murdered in Mexico has drawn the attention of many academics and human rights activists. Some commentators have pointed to social attitudes regarding gender roles as a factor contributing to the high rates of violence against women generally, gay and bisexual men, and transgender women.[181]

Religion

According to the 2010 Mexican Census, approximately 83% of citizens identify themselves as Roman Catholic.[182] Obviously, Catholic individuals hold diverse beliefs, but the Catholic Church hierarchy in Mexico has historically failed to support increased rights for women and has actively campaigned against rights for LGBT people.[183] The Church has taken a particularly vocal stance against same-sex marriage.[184] Even though same-sex marriage does not directly benefit transgender women, as noted elsewhere in this report, the backlash against the legal recognition of same-sex marriage has greatly increased rates of discrimination and persecution against transgender individuals.

Although non-Catholic Christian churches make up on a small number of the total churches in Mexico, there are still areas of the country in which they are becoming very influential.[185] The first half of the century saw the majority of converts located in urban areas, but gradually this has shifted to rural, poorer, and indigenous communities.[186] These populations are often Jehovah’s Witnesses or members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whose views of LGBT individuals are comparable to that of the Catholic Church; as a result, transgender people often face similar levels of discrimination and persecution from members of those churches as well.[187]

Many religious leaders in Mexico have expressed opposition to LGBT rights. For example, Cardinal Javier Lozano Barragán denounced same-sex marriage, saying it would be like considering “cockroaches” part of a family.[188] After the passage of Mexico City’s same-sex marriage law, the Archbishop of Mexico City, Cardinal Norberto Rivera Carrera, declared that same-sex marriage is one of Mexico’s leading problems along with violence, poverty, and unemployment.[189] Such publicly stated views by prominent figures in the Mexican Catholic Church hierarchy likely contribute to the pervasive anti-LGBT views in Mexican society, given that many Mexican Catholics respect and follow the Church’s teachings.

Economic Marginalization.

Mexico’s federal antidiscrimination laws do not prohibit discrimination on the basis of gender identity. The lack of protection leaves transgender women especially vulnerable to employment discrimination.[193] As a consequence, few legal employment opportunities exist for transgender women. Approximately one out of three gay people in Mexico report that they must remain “in the closet” to avoid being fired from their jobs.[194] But for many transgender women—who largely lack access to gender-confirming health care due to high costs, and are generally denied the ability to change the name and/or gender on ID documents to match their gender presentation[195]—it may be difficult or impossible to hide their transgender status, despite the economic penalty that brings. A fortunate few can work as hairstylists or perhaps open a salon if they have enough money or family support.[196] But many transgender women face such socioeconomic marginalization that they must turn to sex work to survive.[197] This results in yet more violence and persecution from both community members and police.[198]

It should be noted that transgender people cannot simply “hide” who they are and thereby escape persecution by living in accordance with their birth-assigned gender role. Gender dysphoria is a serious condition, recognized by every major medical association, the only treatment for which is to live in accordance with the gender with which they identify, rather than the gender assigned at birth.[190] Attempting to suppress one’s gender identity can have dire health consequences.[191] Moreover, a person’s gender identity is a fundamental component of identity, which cannot be required to be changed or hidden as a condition of protection under asylum laws.[192]

Mexico City prohibits gender identity discrimination and provides a legal mechanism for name and gender changes, but even there, in practice, transgender women still endure rampant employment discrimination.[199] The Coordinating Committee for the Development of Diagnosis and Human Rights Program of the Federal District[200] found that despite formal legal protections, transgender women in Mexico City are still discriminated against and denied their labor rights.[201]

Lack Of Gender-Conforming Identity Documents

As noted, only Mexico City permits transgender people to legally change their name and gender to correspond to their gender identity. Even where such mechanisms are technically available, however, legal name changes are not accessible in practice for many transgender women. This is in part due to “lengthy delays and high costs—at least six months and approximately 70,000 pesos [approximately $7,000 USD] are required, and completion sometimes depend[s] on the ‘good will’ of some civil servants.”[202] Without the ability to obtain a legal name change, transgender women cannot obtain a national voter identification card with a name that reflects their female gender identity.[203] The voter identification card is Mexico’s preferred identification card.[204] It is necessary for exercising the right to vote, to acquire property, and to obtain medical assistance in a public hospital.[205] Being forced to present a voter identification card with an old “male” name on it makes transgender women even more vulnerable to discrimination, abuse, and violence.[206]

Lack Of Adequate Health Care

Transgender women lack adequate health care in Mexico.[207] Many transgender women resist seeking medical help because they must disclose their transgender status and subsequently face hostility and threats of violence from medical providers.[208] Medical care providers often do not want to provide medical attention to transgender patients. Providers have mocked and humiliated transgender patients using offensive language, threats, aggression, and hostility.[209] Consequently, transgender women do not routinely access preventive or emergency care.[210]

In particular, medical care to support gender transition—such as hormones or surgeries—is almost entirely unavailable to most transgender women in Mexico. While medical authorities uniformly recognize the medical necessity of transition-related treatment, such care is not covered under Mexico’s national health plan and licensed providers (for those who can afford to pay out of pocket) are scarce.[211] Even where it is available, such care can be prohibitively expensive for transgender women already suffering the effects of economic marginalization discussed earlier.[212] Without access to gender-affirming medical care, many transgender women permanently damage their skin and muscles by injecting dangerous black-market feminizing liquid silicone or other fillers.[213]

Prevalence Of And Lack Of Treatment For Hiv/Aids

Transgender women are also largely denied access to adequate healthcare for other life-threatening conditions, such as HIV/AIDS.[214] In Latin America, transgender women face the highest prevalence of HIV of any group, with a 35% infection rate.[215] Mexico City has the highest number of documented HIV cases in all of Mexico.[216] Despite these high infection rates, medical treatment for HIV and AIDS is largely unavailable in less urban areas due to prohibitive costs.[217] Even in urban areas that have free antiretroviral drugs available they are usually reserved for the sickest people.[218] Many in Mexican society hold misconceptions about the LGBT community and HIV that further contribute to the widespread stigma associated with both HIV and LGBT people.[219] A national survey found that 59% of Mexicans believe that HIV/AIDS is caused by homosexuality.[220] These misconceptions and stigma exist even among medical providers.[221] In fact, most hospitals view homosexuality as a risk factor for HIV and often discriminate against those who do seek treatment.[222] The Commission on Human Rights in Mexico City (CDHDF) also reported that HIV/AIDS clinics often actively mistreat and discriminate against transgender people living with HIV/AIDS.[223]

Evaluating Asylum Claims Made By Mexican Transgender Women

“I would rather die than live that life. It’s like living in hell. Here I feel like I’m in my refuge, at home. … Here I feel like a person.”

– Anonymous Mexican transgender woman in the United States[224]

When a transgender woman seeks asylum in the United States because she fears persecution in Mexico, an asylum officer or immigration judge must decide whether she qualifies for asylum or any other humanitarian relief. These determinations are extremely difficult to make, since asylum claims by their nature involve events in a foreign country. Frequently there are no available witnesses to the incidents other than the survivor herself. Immigration judges therefore have no choice but to render life or death decisions on the basis of limited information. It is therefore critical that adjudicators consider information that accurately reflects the reality of life in Mexico for transgender women.

Unfortunately, a number of misperceptions exist about the conditions for LGBT people, particularly transgender women, in Mexico. Since inaccurate information about country conditions has the potential to compromise the adjudication of asylum claims, it is essential to examine common tropes carefully to determine whether they are accurate. Additionally, it is vital for adjudicators to remember that transgender women in Mexico make up a particular social group that is distinct from gay men (though transgender women are frequently mistaken for feminine gay men). While conditions related to LGBT Mexicans generally may be relevant, adjudicators must address evidence that specifically relates to persecution of the particular social group at issue, transgender women in Mexico. The importance of not conflating the social group of transgender women with other potentially less persecuted members of the LGBT community is equally true in the contexts of transgender asylum seekers from countries other than Mexico.

The Effect Of Same-Sex Marriage And Anti-Discrimination Laws On Violence

As noted above, Mexico began recognizing same-sex marriages throughout the country in 2011. Recently enacted laws also prohibit discrimination on the basis of “sexual preference,” and Mexico City law also prohibits gender identity discrimination. Based on these changes in the law, some immigration judges have mistakenly concluded that LGBT people no longer face homophobic and transphobic violence in Mexico. Instead, the advances in LGBT rights has caused a nationwide backlash from those who oppose the changes, resulting in increased levels of persecution against transgender women who tend to be the most visible and marginalized members of the LGBT community.[225]

Although Mexico’s prohibition of anti-gay discrimination and enactment of some formal protections for same-sex couples may appear to show that authorities are willing to attempt to prevent anti-gay abuse, this does not necessarily translate into them actually being capable of protecting LGBT people generally or transgender women specifically from the horrific violence they face.

Homophobic and anti-transgender violence continues to be rampant in Mexico, including Mexico City. Indeed, Mexico City has the highest rate of transphobic murders in the country. Just as the adoption of laws prohibiting violence against women generally has failed to end the rampant abuse of non-transgender women in Mexico, prohibitions on anti-gay discrimination have not diminished attacks on LGBT Mexicans. In fact, the evidence suggests that same-sex marriage and other formal legal protections have actually made homophobic and transphobic violence worse by inciting a backlash from people opposed to LGBT rights.

Relocation Presumption

Some immigration judges, citing the changed laws in Mexico City, hold that asylum-seekers can return to Mexico and relocate to Mexico City without fear of persecution.[226] As discussed above, however, formal changes in laws permitting same-sex couples to marry and adopt children have not improved conditions for transgender women in Mexico City. In fact, rates of violence and murder have actually increased in Mexico City as well as throughout the nation since the changes in same-sex marriage and adoption laws.

Police harassment against the LGBT community remains high in Mexico City as well. Despite the reputation of the Zona Rosa district of Mexico City as an LGBT neighborhood,[227] extortion and harassment particularly of transgender women continues there.[228] As described above, Mexico City also has the highest rate of transphobic murders in the country. Moving to Mexico City will therefore not protect transgender women from persecution: they will remain vulnerable no matter where they reside in Mexico.

Gay Pride Marches And “Gay Tourism”

Gay pride demonstrations began in Mexico City in 1979. Now, Mexico City hosts a gay pride march each year in the Zona Rosa. Despite this, the violence against the gay community has not ceased or even decreased. According to the Citizens’ Commission against Hate Crimes, there are on average three homophobic murders each month in Mexico.[229]

Moreover, there are significant differences between gay pride parades in the United States and gay pride marches in Mexico City, and the two should not be conflated. According to Professor Victor Clark-Alfaro, the purpose of gay pride marches in Mexico is to bring awareness to and to protest violence and abuse faced by LGBT communities in Mexico. He notes that in assessing country conditions some immigration judges have alluded to gay pride marches being like “parties.” Mr. Alfaro clarified, “They were trying to say it was a fun parade, but in reality it was a protest.”[230]

Another common misperception relates to the significance of “gay tourism” and its implication for the domestic LGBT community in Mexico, particularly transgender people. In asylum cases, government attorneys sometimes submit as evidence of country conditions news articles and blogs about how “gay-friendly” parts of Mexico are for foreign tourists.[231] Some immigration judges have found these online articles and blogs to be persuasive and indicative of improved country conditions for LGBT people in Mexico and cited them when denying transgender women’s asylum claims.

Although tourism constitutes a large part of the Mexican economy, the existence of some tourist destinations that cater to wealthy gay men from other countries is not and could not plausibly be indicative of the safety of low-income Mexican transgender women against hate crimes and violence. Tourism guides do not constitute journalism or human rights reporting, but instead serve the purpose of promotional materials to attract wealthy non-transgender foreigners to spend money at particular clubs and hotels.[232] Even foreign tourists have suffered horrific hate crimes; in one example, Ronald Bentley Main, a real-estate agent and former president of the Greater Seattle Business Association, and his partner, Martin Orozco Gutierrez, were found stabbed to death in Martin’s home in Chapala, Mexico, a city just outside of Guadalajara.[233]

It is important to remember that conditions for tourists are very different from the experience of ordinary Mexican citizens. And the conditions for gay tourists are completely separate from the experiences of transgender Mexican women living in Mexico.[234] News articles about “gay tourism” are not evidence of the day-to-day experiences of gay or transgender Mexican citizens. Most Mexican transgender women do not have the financial security to go to expensive nightclubs, hotels, or resorts that cater to rich, white, gay foreigners.[235] Using tourist gay travel guides as country conditions evidence turns opinion and off-the-cuff remarks into documented fact, allowing flimsy and generalized assertions to become the basis for legal conclusions.[236] This type of “evidence” should not be given credence in asylum cases involving transgender women.

Conditions For Transgender Women In U.S. Immigration Detention Facilities

Many transgender women who flee sexual violence in their home countries face further abuse when seeking asylum in the United States.[237] LGBT immigrants in immigrant detention facilities are exposed to an increased risk of mistreatment, much like LGBT inmates in prison, who studies show are 13 to 15 times more likely than other inmates to be sexually assaulted.[238] After receiving information on gay and transgender individuals who have faced solitary confinement, torture, and mistreatment, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment declared that the treatment of LGBT immigrants in U.S. detention facilities was a violation of the Convention Against Torture.[239]

Since many transgender women seek asylum after experiencing extreme violence in their countries of origin, they are especially vulnerable to the mental health strain of being held in detention.[240] Studies show that detention is a threat to the psychological health of immigrants and can worsen the intense psychological distress often carried by asylum-seekers fleeing persecution.[241] Asylum cases also generally take longer to resolve than other removal cases, leading asylum-seekers to spend more time in immigration facilities than other immigrants.[242] While the average length of stay for an immigrant in detention is 30 days, the average length for asylum-seekers is 102.4 days.[243] Some transgender women have been detained for years while fighting their asylum cases.[244]

Heartland Alliance’s National Immigrant Justice Center filed a report in 2011 documenting the nationwide mistreatment of immigrant transgender women held in detention.[245] The report indicated a systematic problem of ill-treatment, and included complaints by transgender women of sexual assault, denial of medical care, extended periods of solitary confinement, discrimination and abuse, and an ineffectual grievance and appeals process.[246] Transgender women in detention also face mistreatment because they are typically confined with men, where they are regularly subject to abuse by detained men and guards and denied access to healthcare, and where their identities are fundamentally dishonored.[247] Despite ICE’s issuance of a “Transgender Care Memorandum” in 2015,[248] the memorandum entirely lacks enforceability: signing onto the contact modification is optional for facilities. As of March 2016 no facilities have signed a modification to their contacts to permit transgender women to be housed with cisgender women.

A 2010 report by Human Rights Watch regarding sexual assault in immigrant detention facilities found that instances of people detained by ICE being sexually assaulted, abused, and harassed “cannot be dismissed as a series of isolated incidents” and concluded that “there are systemic failures at issue.”[249] The American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2011 upon discovering that nearly 200 cases of sexual assault had taken place in ICE detention facilities since 2007.[250]

Many facilities send transgender immigrants to solitary confinement in order to isolate them from the general population, an effort that may be intended in some cases to protect them from the near-pervasive violence and sexual assault they face.[251] However, solitary confinement frequently results in a number of negative psychological effects, including “hyper-sensitivity to external stimuli, hallucinations, panic attacks, obsessive thoughts, and paranoia[,]”[252] as well as “impulsive, self-directed violence.”[253] Even after release from solitary confinement, those effects linger, and they can permanently damage an individual’s ability to function.[254]

The U.N. Special Rapporteur on torture has stated that the psychological effects of solitary confinement may become irreversible after 15 days.[255] There have been many reports of transgender women being held in isolation in detention facilities for much longer, however. For example, advocates from the organization Americans for Immigrant Justice reported that transgender immigrants detained at the Krome Service Processing Center in Miami, Florida were being held in solitary confinement for periods of up to six months at a time.[256] Other transgender women have reported being subjected to solitary confinement even longer.[257]

María, a Mexican transgender woman who fled persecution in Mexico City, reported that the five months in 2010 that she spent in immigration detention, where she was kept in solitary confinement, were “true hell.”[258] Detained transgender women are frequently held in isolation for up to 23 hours a day, “often without access to library resources, telephones, outdoor recreation, religious services, or legal services that are otherwise available to other people.”[259] A counselor at a New Jersey detention center reported that “the treatment of people in solitary confinement is inhumane. There are many violations of human rights. One of them is that inmates in solitary confinement are forced to take tranquilizers in order to keep them calm.”[260] Many transgender women have given up on their very strong asylum cases because their detention conditions were too unbearable to withstand, especially on top of the trauma that they already suffered from their experiences in Mexico. The New Jersey counselor also reported that during the first trimester of 2013, at least 10 transgender women in the facility were pressured into signing voluntary deportation documents.[261]

Transgender women in detention facilities also often face a lack of access to adequate medical treatment.[262] HIV-positive transgender women are particularly vulnerable.[263] Victoria Arellano, an HIV-positive transgender woman, died in 2007 while being held in a large men’s detention cell in an ICE facility after authorities refused to provide her with medical attention and her medication.[264] As recently as November 2014, there were still reports of transgender women living with HIV being denied access to HIV medication.

Transgender immigrants in detention are also commonly denied all gender-confirming medical treatment, including hormone therapy, which many United States Courts of Appeal have found must be provided to prisoners diagnosed with gender dysphoria under the Eighth Amendment’s guarantee of basic medical care for incarcerated individuals.[265] Although ICE’s Performance-Based National Detention Standards provide for access to hormone therapy for transgender women who had already been receiving hormone therapy before being detained, these guidelines are seldom followed.[266] One Mexican transgender woman held in immigration detention at the Santa Ana City Jail reported being refused hormone therapy, which she had been on for the past 10 years.[267] Distraught, and not receiving treatment for trauma-related depression, she attempted suicide.[268] Following her suicide attempt, authorities put her in solitary confinement.[269]

While in detention, transgender women also face instances of mistreatment and humiliation from facility staff and ICE personnel.[270] One transgender woman held in Theo Lacy Facility in California reported that she was called a “faggot” by guards on a number of occasions, and was also mocked because she was dying of AIDS.[271] Moreover, guards singled her out for public searches where they forced her to undress and then ridiculed her bare breasts.[272] When staff members are themselves the source of abuse against transgender women, “protective” measures such as solitary confinement are particularly ineffective.[273]

Surveys conducted by the Department of Justice have found that LGBTQ people face much higher rates of sexual assault than other incarcerated people.[274] Another study found that transgender women in male prisons are 13 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than the general population, with 59% reporting experiencing sexual assault.[275] Although transgender women only account for 1 out of 500 detained immigrants, one out of every five confirmed cases of sexual assault in ICE facilities involved transgender survivors.[276] Incidents include a case of a guard who sexually assaulted a transgender woman while she was in “protective custody.”[277] Another reported incident involved an ICE officer who forced a transgender woman to remove her shirt while he ejaculated into a cup and demanded that she drink his semen.[278] The officer admitted to the abuse, but served only two days in a county jail, while the victim remained locked with men in ICE detention for another five months.[279]

Johanna, a transgender woman from El Salvador, left for the United States after she was gang-raped.[280] After living in the U.S. for 12 years, Johanna was apprehended by ICE and placed in an all-male detention facility.[281] While in the facility, Johanna was sexually assaulted by another detained immigrant.[282] Unable to bear the conditions of her detention, Johanna agreed to be deported.[283] She would flee again to the United States two more times.[284] Each time she faced sexual abuse in all-male ICE detention facilities and months of solitary confinement. Johanna ultimately won withholding of removal due to the severe violence and persecution she experienced in El Salvador.[285] If she had been released or if alternatives to detention had been used in the first instance, Johanna would have been spared repeated sexual assaults and months of solitary confinement she suffered in U.S. custody.

Although in recent years the Department of Homeland Security has stated an intention to improve the treatment of LGBT immigrants in its custody, transgender women continue to be subjected to horrific treatment by ICE.[286] For example, in 2014, Marichuy Leal Gamino, a 23-year-old transgender woman originally from Mexico, was detained with men at the Eloy Detention Center. Gamino faced repeated instances of mistreatment, culminating in a sexual assault by her cellmate.[287] After reporting the abuse to the staff of the facility, she said that they tried to get her to sign a statement saying that she consented to the sexual assault.[288] This series of events occurred nine years after the passage of the Prison Rape Elimination Act and nearly a year after DHS announced its regulations to implement the Act, which include explicit protections for transgender immigrants.[289]

Many detained transgender women continue at the time of this writing to experience transphobic abuse from guards, denial of HIV medicine and hormones, being forced to shower with men, sexual violence from guards and other detained immigrants, and solitary confinement.[290] Detention conditions for transgender women are both a human rights and access to justice concern. When transgender women give up on their asylum claims under existing immigration law solely because detention conditions are unbearable, this is a grave obstacle to fair adjudication.

Recommendations