At These Powwows, Two-Spirit People Are Always Revered

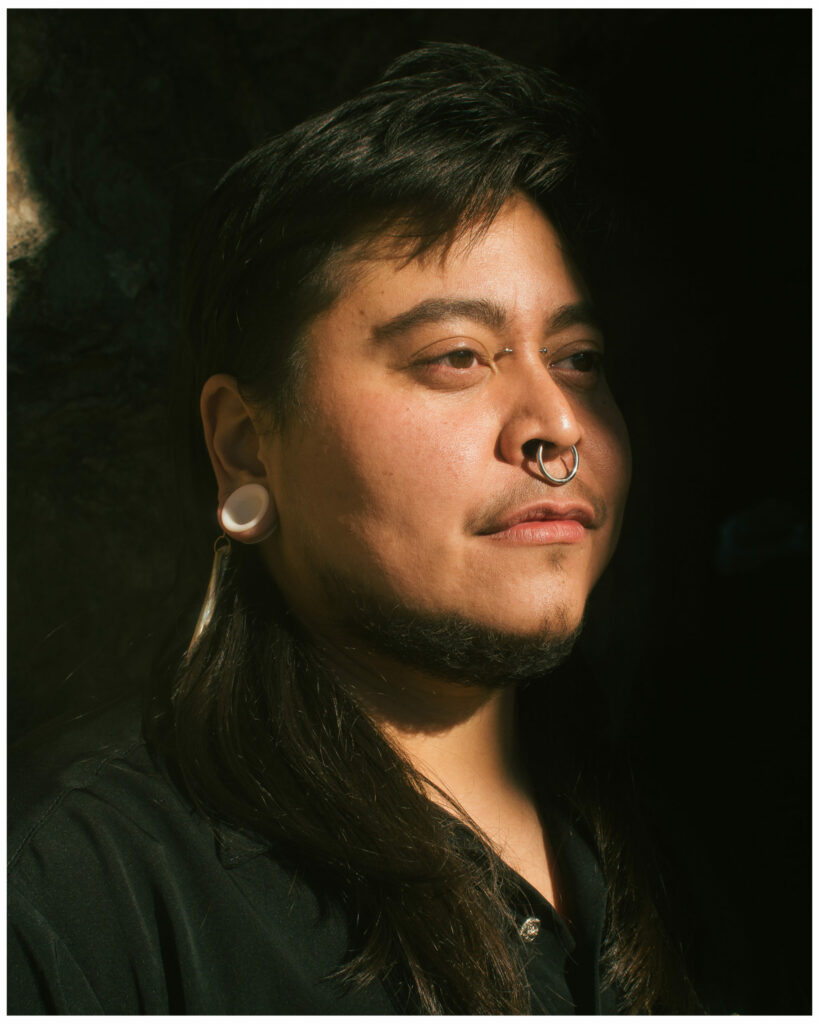

Photo of Faun Harjo by Vilerx Pérez.

Faun Harjo felt clammy and hot under his regalia. The June air was thick with dust and smoke from the wildfires that were then raging across the West Coast; as the sun filtered through the ash, the sky glared neon pink with dark gray streaks. Internally, he was panicking as he prepared to dance Southern Traditional (Watch on YouTube) — a powwow style he had never performed publicly — for a crowd at the 2021 Montana Two-Spirit gathering.

“Everything’s on fire around us, and everything looks very alien,” he laughs, recalling the day. “Didn’t make it particularly easier to not be scared.”

He had never danced powwow, let alone worn men’s regalia while doing so, but today he was going to make his auntie proud. Of course, there’s added pressure when your auntie is Landa Lakes, co-founder of the Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS), one of the largest Two-Spirit organizations in the country. With his heart beating out of his chest and blood roaring in his ears, Harjo adjusted the porcupine roach atop his head and stepped forward.

Prior to this weekend, the closest Harjo had gotten to performing at a powwow was shaking shells and wearing a Chickasaw dress as a baby, a role typically reserved for girls and women. Like everyone else at the 2021 gathering, however, Harjo, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) and Chickasaw nations, is Two-Spirit, an umbrella term popularized in the ‘90s by Native activists to describe gender identities that don’t conform to a Western binary (Watch on YouTube) across the Indigenous nations of Turtle Island and beyond.

This excerpt is from “At These Powwows, Two-Spirit People Are Always Revered” a story by them highlighting systemic violence and barriers that Indigenous trans, Two-Spirit, and gender-variant Pasifika people face — and the movements to overcome them.

“The history of our Native LGBTQ communities when colonizers came in, they had this religious mentality. And when they saw same-sex partners or if they saw people who were who were living as women who they felt were men, in their eyes they were thought of as evil and not right. So throughout history, our populations were erased or put in a negative context with literature and I tell people anthropology is one-sided. It’s always their side when you look at things.” — Mattee Jim, Navajo