Findings on state and interpersonal violence from a national needs assessment of transgender and gender non-conforming people living with HIV.

Suggested citation: Chung, Cecilia; Kalra, Anand; McBride, Beatrix; Roebuck, Christopher; and Laurel Sprague. (2016). See us as people: findings on state and interpersonal violence from a national needs assessment of transgender and gender non-conforming people living with HIV. Oakland, CA: Transgender Law Center

Introduction + Background

In August 2015, Positively Trans, a project of Transgender Law Center, held focus groups with transgender women of color living with HIV in Atlanta, Georgia and Miami, Florida. The purpose of the groups was to generate information to illustrate –with real experiences and stories—the resilience, challenges, and barriers our community faces. Meant to supplement and parallel our quantitative study, the focus groups produced deep and meaningful conversations that policymakers too often ignore or simply never hear.

While discussing changes in the legal and policy environment, focus group participants brought up the shortcomings of policies that would protect transgender people in theory, but fall short in practice because of a lack of enforcement. Too often, arms of the state meant to protect civil and human rights instead become instruments of harm against our communities. The ongoing violence transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) people face is a result of persistent dehumanization of TGNC people, and trans people living with HIV (TPLHIV) are at heightened risk, due to family rejection and rampant discrimination in housing, health care, education, and employment.[1] [2] [3] [4] As a result, TGNC people, especially transgender women of color, find themselves cut out of the formal economy without access to safe, respectful health care, which in turn creates increased vulnerability to abuse from law enforcement and the judicial system.[5] [6] [7]

Transgender people experience interpersonal violence at higher rates than the general population. Nearly one fifth of trans people living in the United States have experienced domestic violence by a family member because of the fact that they are trans.[8] Nearly 60% of trans people have reported rejection from family members, which is correlated with much higher rates of homelessness, HIV, and suicide attempts.[9] Trans women are almost twice as likely to experience sexual violence than the general population.[10] Over 40% of trans people have reported physical violence due to the fact that they are transgender.[11] Transgender people of color report even higher rates of physical violence due to being transgender.[12] Other factors, such as participation in sex work, increase the risk of interpersonal violence for transgender people, with 65% of trans women participating in sex work in Washington, DC, reporting violence from both customers and police.[13]

While we know these heartbreaking statistics for the general transgender population, studies of transgender people living with HIV rarely go beyond transmission risk and surveillance data, hindering a holistic understanding of TPLHIV’s lives that could identify the role of violence and discrimination in creating the conditions that result in the extreme HIV prevalence rates these studies do observe – with estimates at high as 27% for transgender women overall and above 50% for African American transgender women.[14]

Transgender Law Center launched Positively Trans as a project that focuses on the development of leadership, self-empowerment, and advocacy by and for transgender people living with HIV. Positively Trans operates under the guidance of a National Advisory Board (NAB) of transgender people living with HIV from across the United States; the NAB is primarily composed of trans women of color who are already engaged in advocacy and leadership roles in their local communities. In order to identify community needs and advocacy priorities, we conducted a quantitative needs assessment in the summer of 2015, which was distributed online in Spanish and English. Responses were limited to adults living with HIV in the U.S. whose sex at birth is different from their current gender identity. The project was reviewed and given exempt status by the Eastern Michigan University Institutional Review Board.

In the face of these systemic threats and barriers to autonomy and wellbeing, the impact of HIV on the transgender community cannot simply be addressed by programs that work to affect individual behaviors; we must address the systemic barriers our community members face—and the complex interactions of these systems—to reduce HIV risk and increase access to care and other resources for trans people living with HIV (TPLHIV). We believe that effective HIV responses for transgender people must include a combination of leadership development, community mobilization and strengthening, access to quality health care and services, and policy and legal advocacy aimed to advance the human rights of the community. Furthermore, we believe that an effective HIV response for trans people must center the leadership, voices, and experiences of TPLHIV, particularly trans women of color.

Our communities need substantive and dramatic change in the hearts and minds of people writing and enforcing public policy. As one participant in the Atlanta focus group put it: “They have to see us as people in order to consider protecting us in a way that matters.”

Findings

In all, over 400 people attempted the survey; 80% of complete responses came from the English version, and 20% from the Spanish version. Findings below represent analysis from 157 complete, valid responses. Based on responses to several items on the survey instrument, we expect that the survey mostly attracted respondents who already have access to medical care (for example, 77% of respondents were virally suppressed). As a result, the responses may understate the experiences of those who are more isolated. Significantly, the survey did not reach respondents who are currently incarcerated; we expect that including incarcerated people in the study would shift findings dramatically. Because respondents were recruited through existing networks and not randomly selected, the results cannot be interpreted as representative of all transgender people living with HIV in the U.S. Instead, these results should be understood as illustrating the experiences and priorities of transgender people living with HIV and as providing a starting point for further engagement.

The majority of respondents were female-identified U.S. citizens making less than $23,000 per year. More than 40% had been incarcerated in their lifetime and 42% currently live in the South. The median length of time since identifying as transgender/ gender non-conforming was 5 years greater than the median length of time living with HIV, suggesting that transgender and gender non-conforming people face unique risk and vulnerability to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Table 1 contains a summary of demographic information for respondents who submitted complete surveys. Descriptive statistics of respondent demographics suggest that the survey oversampled whites and undersampled young people and people living in the Northeast.

In our initial report, we provided detailed demographics on the survey sample. Tables 1 and 2 show a few demographics, divided by key characteristics. Trans women, Southern respondents, and trans women of color were much more likely to report earning less than $12,000 annually than their counterparts (p<0.01). Trans women, trans women of color, respondents of color overall, and Spanish-language respondents were significantly less likely to have received a college degree (p<0.005), but education level was not affected by region. More than two thirds of the sample were people of color, with highest density among Spanish-language respondents (100%), Southern respondents (82%), and low-income respondents (78%).

Table 1: Summary of Sample Demographics by Race and Gender

| All | Gender | Race | Trans Women of Color | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans Women | Trans men | Resp. of Color | White Resp. | TWOC | All Other | ||||||

| (N=157) | (N=132) | P | (N=18) | P | (N=107) | (N=50) | P | (N=96) | (N=61) | P | |

| % of total sample | 100% | 84% | NA | 11% | NA | 68% | 32% | NA | 61% | 39% | NA |

| % Resp. of color | 68% | 73% | 0.005 | 33% | <0.001 | 100% | 0% | <0.001 | 100% | 18% | <0.001 |

| % Ann. Income <$12,000 | 43% | 48% | 0.001 | 6% | 0.002 | 49% | 30% | 0.043 | 52% | 28% | 0.003 |

| All | Gender | Race | Trans Women of Color | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans Women | Trans men | Resp. of Color | White Resp. | TWOC | All Other | ||||||

| (N=157) | (N=132) | P | (N=18) | P | (N=107) | (N=50) | P | (N=96) | (N=61) | P | |

| Outlying stats | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.008 | <0.001 | |||||||

| No Formal Education | 3% | 2% | NA | 0% | NA | 3% | 2% | NA | 2% | 3% | NA |

| Less than HS/GED | 12% | 14% | NA | 0% | NA | 16% | 4% | NA | 18% | 3% | NA |

| HS Diploma/GED | 22% | 26% | NA | 0% | NA | 26% | 14% | NA | 28% | 13% | NA |

| Some College | 36% | 36% | NA | 50% | NA | 36% | 36% | NA | 35% | 36% | NA |

| College Degree | 20% | 19% | NA | 22% | NA | 16% | 28% | NA | 1% | 28% | NA |

| Graduate degree | 8% | 3% | NA | 28% | NA | 4% | 16% | NA | 2% | 16% | NA |

Table 2: Summary of Sample Demographics by Region and Income

| All | Region | Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | Other | <$12,000 Ann. | >$12,000 Ann. | ||||

| (N=157) | (N=66) | (N=91) | P | (N=67) | (N=90) | P | |

| % of total sample | 100% | 42% | 58% | NA | 43% | 57% | NA |

| % Resp. of color | 68% | 82% | 58% | 0.002 | 78% | 61% | 0.028 |

| % Ann. Income <$12,000 | 43% | 58% | 32% | 0.002 | 100% | 0% | < 0.001 |

| All | Region | Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | Other | <$12,000 Ann. | >$12,000 Ann. | ||||

| (N=157) | (N=66) | (N=91) | P | (N=67) | (N=90) | P | |

| Outlying stats | 0.374 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No formal education | 3% | 3% | 2% | NA | 3% | 2% | NA |

| Less than HS/GED | 12% | 17% | 9% | NA | 25% | 2% | NA |

| HS diploma/GED | 22% | 27% | 19% | NA | 28% | 18% | NA |

| Some college | 36% | 29% | 41% | NA | 36% | 36% | NA |

| College Degree | 20% | 18% | 21% | NA | 6% | 30% | NA |

| Graduate degree | 8% | 6% | 9% | NA | 1% | 12% | NA |

State Violence

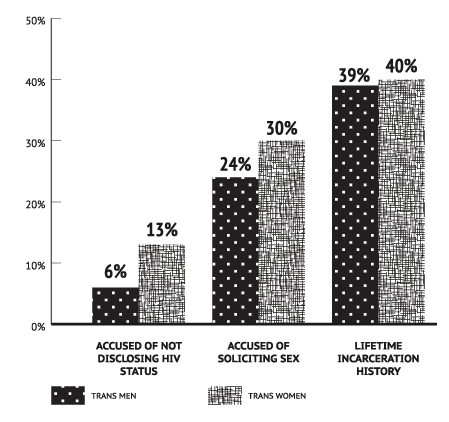

Items measuring state violence included interactions with police, legal accusations (not disclosing HIV status, soliciting sex, and loitering or being a public nuisance), history of incarceration in any setting (e.g., jail, prison, immigration detention), and belief that respondent would get a fair hearing if accused of a crime. Overall, 41% of respondents reported having been incarcerated at least once in their lifetimes – this alarming number did not differ significantly based on race, gender, region, or income, indicating that TGNC people are not only at risk of incarceration at an incredibly high rate, but that the circumstances surrounding their incarceration are different than for non-transgender people (i.e., in cisgender populations, rates of incarceration do vary by race, gender, income, and region ). The robustness of the finding against demographic categories adds credence to the numerous anecdotal reports of police profiling TGNC people as well as TGNC people being in high-risk situations at higher rates than their non-transgender counterparts.

Fig. 1 – Legal Accusations and Incarceration by Gender Identity

In our sample, 29% of respondents reported having been legally accused of soliciting sex at least once in their lives. Again, this rate was robust against all demographic breakdowns, including gender, with 22% of transgender men reporting facing legal accusation of soliciting sex. Trans women of color and low-income respondents had rates above their counterparts, but the differences were not statistically significant. In addition, 18% of respondents reported legal accusations for loitering or being a public nuisance; trans women of color were less likely to report this accusation than their counter parts (15% vs 24%, p = 0.078). Nearly one in seven respondents (14%) reported facing a legal accusation of not disclosing their HIV status; this finding was also stable across all groups.

One in four respondents have been physically assaulted by a police officer because they are transgender or gender non-conforming, stable across gender, region, and race. Low-income respondents were more likely to have experienced transphobic physical assault by a police officer (30% vs 18%, p <0.1). Additionally, 7% of respondents reported physical assault by a police officer because of their HIV status. Further, more than a quarter (26%) of respondents reported that a police officer had disclosed their transgender status without their consent.

Given the rampant police abuse and entanglement with the legal system in our sample, it was unsurprising to find that 27% of respondents believed they “definitely could not get a fair hearing if accused of a crime” (this item used a 4-degree Likert scale). People of color (36%), transwomen of color (35%), Southern respondents(41%), and Spanish-language respondents (61%)were more likely to report lack of faith in a fairhearing (p<0.005), as were trans women overall(29%, p<0.05).

Table 3: Experience with Legal system, law enforcement, and incarceration by Race and Gender

| All | Gender | Race | Trans Women of Color | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans women | Trans men | Resp. of Color | White Resp. | TWOC | All Other | ||||||

| (N=157) | (N=132) | P | (N=18) | P | (N=107) | (N=50) | P | (N=96) | (N=61) | P | |

| Transphobic Physical Assault by police officer | 25% | 24% | 0.890 | 20% | 0.502 | 24% | 20% | 0.551 | 25% | 20% | 0.439 |

| Serophobic Physical Assault by police officer | 7% | 6% | 0.286 | 6% | 0.798 | 7% | 6% | 0.736 | 7% | 7% | 0.861 |

| Police officer outed transgender status without consent | 26% | 25% | 0.465 | 39% | 0.190 | 29% | 20% | 0.233 | 28% | 23% | 0.472 |

| All | Gender | Race | Trans Women of Color | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans women | Trans men | Resp. of Color | White Resp. | TWOC | All Other | ||||||

| (N=157) | (N=132) | P | (N=18) | P | (N=107) | (N=50) | P | (N=96) | (N=61) | P | |

| Accused of not disclosing HIV status | 14% | 13% | 0.594 | 6% | 0.331 | 13% | 12% | 0.850 | 11% | 15% | 0.546 |

| Accused of soliciting sex | 27% | 28% | 0.679 | 22% | 0.601 | 30% | 22% | 0.301 | 31% | 21% | 0.174 |

| Accused of loitering or being a public nuisance | 18% | 14% | 0.010 | 33% | 0.068 | 17% | 20% | 0.628 | 14% | 25% | 0.078 |

| Believe could not get fair hearing if accused of a crime | 27% | 29% | 0.185 | 6% | 0.031 | 36% | 8% | 0.001 | 35% | 13% | 0.002 |

| History of Incarceration | 41% | 40% | 0.465 | 39% | 1.000 | 42% | 40% | 0.808 | 41% | 43% | 0.804 |

Table 4: Experience with Legal system, law enforcement, and incarceration by Region and Income

| All | Region | Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | Other | <$12,000 ann. | >$12,000 ann. | ||||

| (N=157) | (N=66) | (N=91) | P | (N=67) | (N=90) | P | |

| Transphobic Physical Assault by police officer | 25% | 26% | 24% | 0.245 | 30% | 18% | 0.912 |

| Serophobic Physical Assault by police officer | 7% | 10% | 6% | 0.276 | 12% | 3% | 0.467 |

| Police officer outed transgender status without consent | 26% | 30% | 23% | 0.309 | 30% | 23% | 0.120 |

| All | Region | Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | Other | <$12,000 ann. | >$12,000 ann. | ||||

| (N=157) | (N=66) | (N=91) | P | (N=67) | (N=90) | P | |

| Accused of not disclosing HIV status | 14% | 12% | 15% | 0.660 | 9% | 16% | 0.097 |

| Accused of soliciting sex | 27% | 24% | 30% | 0.452 | 33% | 23% | 0.187 |

| Accused of loitering or being a public nuisance | 18% | 12% | 22% | 0.111 | 18% | 18% | 0.433 |

| Believe could not get fair hearing if accused of a crime | 27% | 41% | 16% | 0.001 | 28% | 26% | 1.000 |

| History of Incarceration | 41% | 45% | 38% | 0.475 | 37% | 44% | 1.000 |

Table 5: Interpersonal Violence by Race and Gender

| All | Gender | Race | Trans Women of Color | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans Women | Trans Men | Resp. of Color | White Resp. | TWOC | All other | ||||||

| (N=157) | (N=132) | P | (N=18) | P | (N=107) | (N=50) | P | (N=96) | (N=61) | P | |

| Kicked out of family before age 18 because TGNC | 27% | 26% | 0.518 | 33% | 0.503 | 30% | 20% | 0.266 | 30% | 21% | 0.220 |

| Excluded from family events because TGNC | 39% | 41% | 0.225 | 33% | 0.610 | 40% | 36% | 0.616 | 42% | 34% | 0.364 |

| Harassed on the street in previous 12 months because TGNC | 59% | 61% | 0.106 | 56% | 0.431 | 64% | 46% | 0.044 | 66% | 48% | 0.025 |

| Phys. assaulted on the street in prev. 12 months because TGNC | 44% | 46% | 0.647 | 36% | 0.886 | 23% | 18% | 0.261 | 27% | 18% | 0.193 |

| Survivor of sexual assault | 49% | 51% | 0.324 | 33% | 0.157 | 50% | 46% | 0.602 | 51% | 46% | 0.530 |

Interpersonal Violence

The survey instrument measured interpersonal violence in a variety of ways; included in this analysis are items on sexual assault, family rejection, and street harassment and assault.

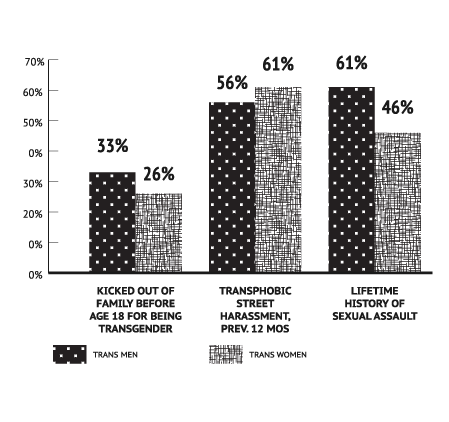

Overall, 49% of respondents reported experiencing sexual assault at least once in their lives. Low-income respondents were more likely to report experiencing sexual assault (58%, p<0.05), and trans men were less likely to report experiencing sexual assault (33%), though this rate was not significantly different at the p<0.1 level (p=0.157). Immigrant respondents were more likely to report having been sexually assaulted (61%, p<0.1). Spanish-language respondents reported a much higher rate of sexual assault than any other group (74%, compared to 43% of English-language respondents, p = 0.002).

Fig. 2 – Interpersonal Violence by Gender Identity

When asked about their experiences in the previous 12 months, 59% of respondents said they had been verbally harassed on the street because of their transgender status. Respondents of color in general and trans women of color specifically were more likely to report experiencing verbal harassment on the street (p<0.05), as were low-income respondents (p<0.1). Our data suggest that these incidents of verbal harassment may often escalate into physical violence, with 44% of respondents reporting being physically assaulted on the street in the previous 12 months because of their transgender status. This rate was relatively stable across groups, with trans men being slightly less likely to have been assaulted (33%, p=0.157) and trans women of color more likely (58%, p=0.131), though neither of these results are significant at the p<0.1 level.

At the root of these issues may be lifelong vulnerability resulting from family rejection and exclusion. More than a quarter of respondents reported that they had been kicked out of their homes for being transgender or gender non-conforming before age 18 (27%). Low-income respondents were more likely to experience this family rejection (36%, p=0.027), suggesting that many transgender people are never able to reach financial stability when required to be financially independent from an early age.

Table 6: Interpersonal Violence by Region and Income

| All | Region | Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | Other | <$12,000 ann. | >$12,000 ann. | ||||

| (N=157) | (N=66) | (N=91) | P | (N=67) | (N=90) | P | |

| Kicked out of family before age 18 because TGNC | 27% | 32% | 23% | 0.299 | 36% | 20% | 0.027 |

| Excluded from family events because TGNC | 39% | 35% | 42% | 0.477 | 37% | 40% | 0.733 |

| Harassed on the street in previous 12 months because TGNC | 59% | 69% | 58% | 0.209 | 67% | 52% | 0.060 |

| Phys. assaulted on the street in prev. 12 months because TGNC | 44% | 37% | 48% | 0.434 | 28% | 20% | 0.222 |

| Survivor of sexual assault | 49% | 49% | 49% | 0.905 | 58% | 42% | 0.047 |

Recommendations

Transgender people living with HIV face a barrage of discrimination and violence in daily life. In order to reduce the risk and to improve the health and quality of life of TPLHIV, we must create opportunities that empower TPLHIV and support their agency to leave the abusive environment behind. We must also provide resources that enable TPLHIV to overcome these barriers.

We recommend:

- Pre-arrest diversion programs to connect TPLHIV with social services and job training

- Economic development to support TPLHIV’s autonomy

- Reform of current criminalization laws that perpetuate stigma and discrimination

- Police reform to sensitize law enforcement officers on trans issues and to foster a safer environment for TPLHIV to report violence and to access victim services.

- Legislation both federally and statewide to protect TPLHIV from transphobia and discrimination

- Fully funded, low- and no-cost, trauma-informed behavioral health and HIV services

Acknowledgments

Transgender Law Center is grateful to the many people who have contributed their time and energy to Positively Trans. Without them, this work would not be possible. In particular, we would like to thank each member, both past and present, of the National Advisory Board:

- Nikki Calma

- Bré Campbell

- Jada Cardona

- Dee Dee Chamblee

- Ruby Corado

- Teo Drake

- Achim Hoaward

- Octavia Lewis

- Arianna Lint

- Tela Love

- Tiommi Luckett

- Jazielle Newsome

- Diana Oliva

- Milan Nicole Sherry

- Kiara St. James

- Channing-Celeste Wayne

- Liaam Winslet

In Addition

We would like to express our thanks to Laurel Sprague, Bré Campbell, Jenna Rapues, Chris Roebuck, Erin Armstrong, Collette Carter, Poz Magazine¸ thebody.com, HIV Plus Magazine, Positive Women’s Network USA, the SERO Project, AIDS United, and AIDS Foundation of Chicago. We are grateful for the generous support of the Elton John AIDS Foundation, Levi Strauss Foundation, MAC AIDS Fund, and the Health Resources Services Administration.

Notes

- Baral, S.D., Poteat, T., Strömdahl, S., Wirtz, A.L., Guadamuz, T.E. and Beyrer, C., 2013. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet infectious diseases, 13(3), pp.214-222.

- Operario, D., Yang, M.F., Reisner, S.L., Iwamoto, M. and Nemoto, T., 2014. Stigma and the syndemic of HIV-related health risk behaviors in a diverse sample of transgender women. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(5), pp.544-557.

- Hartzell, E., Frazer, M.S., Wertz, K., and Davis, M., 2009. The state of transgender California: Results from the 2008 California transgender economic health survey. San Francisco: Transgender Law Center.

- Grant, J., Mottet, L.A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J.L., and Keisling, M. (2011). “Injustice at every turn: a report of the transgender discrimination survey.” Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

- Ibid.

- Stotzer, R.L., 2014. Law enforcement and criminal justice personnel interactions with transgender people in the United States: A literature review. Aggression and violent behavior, 19(3), pp.263-277.

- Bradford, J., Reisner, S.L., Honnold, J.A. and Xavier, J., 2013. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), pp.1820-1829.

- Grant et al. (2011). Injustice At Every Turn.

- Ibid.

- Anti-Violence Project. Hate violence against transgender communities. http://www.avp.org/storage/documents/ncavp_transhvfactsheet.pdf

- Stotzer, R.L., 2009. Violence against transgender people: A review of the United States data. Aggression and violent behavior, 14, pp.170-179.

- Grant, J.M., et al, 2011. Injustice at every turn.

- Stotzer, R.L., 2009. Violence against transgender people.

- Herbst, J. H., Jacobs, E.D., Finlayson, T.J., McKleroy, V.S., Neumann, M.S., and Crepaz, N., 2008. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS and behavior, 12, pp.1-17.

- Carson, E.A. (2015). Prisoners in 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, September 2015, NCJ 248955. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5387

Table 7: Appendix – Demographic Summary and Violence Items, Transgender Men Respondents

| All | Trans Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=157) | (N=66) | P | |

| % of total sample | 100% | 11% | |

| Respondents of color | 68% | 33% | <0.001 |

| Annual Income <$12,000 | 43% | 6% | 0.002 |

| All | Trans Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=157) | (N=66) | P | |

| Outlyers | 0.002 | ||

| No formal education | 3% | 0% | NA |

| Less than HS/GED | 12% | 0% | NA |

| HS diploma/GED | 22% | 0% | NA |

| Some college | 36% | 50% | NA |

| College Degree | 20% | 22% | NA |

| Graduate degree | 8% | 28% | NA |

| All | Trans Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=157) | (N=66) | P | |

| Transphobic Physical Assault by police officer | 25% | 20% | 0.502 |

| Serophobic Physical Assault by police officer | 7% | 6% | 0.798 |

| Police officer outed transgender status without consent | 26% | 39% | 0.190 |

| All | Trans Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=157) | (N=66) | P | |

| Accused of not disclosing HIV status | 14% | 6% | 0.331 |

| Accused of soliciting sex | 27% | 22% | 0.601 |

| Accused of loitering or being a public nuisance | 18% | 33% | 0.068 |

| Believe could not get fair hearing if accused of a crime | 27% | 6% | 0.031 |

| History of Incarceration | 41% | 39% | 1.000 |

| All | Trans Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=157) | (N=66) | P | |

| Kicked out of family before age 18 because TGNC | 27% | 33% | 0.503 |

| Excluded from family events because TGNC | 39% | 33% | 0.610 |

| Harassed on the street in previous 12 months because TGNC | 59% | 56% | 0.431 |

| Phys. assaulted on the street in prev. 12 months because TGNC | 44% | 36% | 0.886 |

| Survivor of sexual assault | 49% | 33% | 0.157 |